Team of Teams by General Stanley McChrystal: Book Summary

Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for A Complex World by United States Army General Stanley McChrystal is an amazing, thoughtful, in-depth discussion of how organizations must move away from chasing efficiency through hierarchical command-and-control.

Instead, McChrystal shows how organizations can achieve their goals through adaptability and by fostering a culture of self-sufficiency that empowers people to make informed decisions across the organization.

In this post, I’ll cover some of the main points in the book. It’s a great read for business leaders.

McChrystal is probably best known for tracking down and eliminating Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. McChrystal chronicles his experience and lessons learned as he commanded the Joint Special Operations Command from 2003 to 2008 that brought down Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

The book takes lessons learned from that experience and weaves in discussions around the history and theory of how best to run a business (namely Taylorism), and how leadership teams today need to change their approach for best results.

As General McChrystal states:

“This isn’t a war story, although our experience in the fight against Al Qaeda weaves through the book. Far beyond soldiers, it is a story about big guys and little guys, butterflies, gardeners, and chess masters.”

McChrystal inherited a military infrastructure in the form of the Combined Joint Task Force. They were fighting an enemy in Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) that were poorly-trained and under-resourced. And that enemy was winning.

Part I

“This was not a war of planning and discipline; it was one of agility and innovation.”

19th and 20th century approaches to military organization no longer applied at the turn of the millennium

Rigid, standardized, and hierarchical structures were soon to prove outmoded

Responding to an incredibly complex world requires flexibility

In complex systems, actions are amplified unpredictably

On paper, Task Force vs AQI should have been no contest. The Task Force brought together the best of the best. Why were they losing? The Task Force struggled to understand an enemy with no fixed location, no uniforms, shifting identities, and cyberspace channels to recruit and deploy propaganda. This was unlike any war fought in the 20th century.

“We had more in common with the plight of a Fortune 500 company trying to fight off a swarm of start-ups than we did with the Allied command battling Nazi Germany in WWII.”

In 2004, insurgency, terrorism, and radicalization were being combined with new technologies to create an entirely new problem set. AQI acted like a shape-shifter. They weren’t the biggest or strongest, but they transformed at will.

This environment was not conducive to what the military machine had been built to do. McChrystal writes, “How do you train the leviathan to improvise?”

Team of Teams. Source: Gen Stanley McChrystal et al., Team of Teams, page 25

He outlines the example of Admiral Nelson, famous commander of the British Navy in the 18th century.

Nelson understood that in the heat of battle, communication lines get disrupted. He built up the capabilities of the captains on each of his ships because they needed to act on their own initiatives. His captains were to see themselves as “entrepreneurs of battle.” And, it worked. Nelson’s fleet secured huge victories over the French and Spanish fleets, helping establish England as a world power.

In applying this lesson to the 21st century, McChrystal had his work cut out for him. Here’s how he did it:

“We restricted our force from the ground up on principles of extremely transparent information sharing (what we call “shared consciousness”) and decentralized decision-making authority (“empowered execution”). We dissolved the barriers - the walls of our silos and the floors of our hierarchies - that had once made us efficient. We looked at the behaviors of our smallest units and found ways to extend them to an organization of thousands, spread across three continents. We became what we called “a team of teams”: a large command that captured at scale the traits of agility normally limited to small teams.”

The industrial revolution led to the pursuit of efficiency at all costs. McChrystal and the Task Force learned that “adaptability must become our central competence.”

“Interconnectedness and the ability to transmit information instantly can endow small groups with unprecedented influence: the garage band, the dorm-room start-up, the viral blogger, and the terrorist cell.”

There were good reasons why the military was setup the way it was.

“Standardization and uniformity have enabled military leaders and planners to bring a semblance of predictability and order to the otherwise crazy environment that is war.”

A good example of something seemingly small, like a soldier packing their gear consistently and correctly: “Under fire and often in the dark, Rangers must be able to locate water, gauze, and ammunition in seconds. A correctly packed bag can mean the difference between life and death.”

McChrystal refers to the example of Frederick Winslow Taylor, a 19th century Quaker known as the “father of scientific management.” His thinking brought the scientific method to the civilian sector.

Taylor found a way to churn out more metal chips per minute than anyone else. Where 9 feet per minute was the norm, Taylor’s system could cut 50. Industrial manufacturing was sexy in the 19th century. Taylor’s revolutionary procedures were akin to Steve Jobs introducing the iPhone.

Taylor’s genius was in his strict procedures. His vision was a “clockwork universe” where all causes and effects were predictable; reductionism broke down everything to its simplest elements. He made more, faster, with less.

Under Taylor’s system, there was a hard and fast line between thought and action: “managers did the thinking and planning, while workers executed.”

Military planners throughout the 19th and 20th centuries relied on many of Taylor’s strategies. By the dawn of the 21st century, McChrystal realized this approach was no longer working.

“The new world required a fundamental rewriting of the rules of the game…the proliferation of new information-age technologies rendered Taylorist efficiency an outdated managerial paradigm…Managerially, AQI was flanking us.”

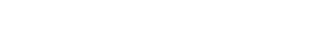

“Complex” is different from “complicated.”

Understanding this difference was key to the new approach McChrystal pursued as commander of Task Force. The following quotes illustrate his understanding.

“Things that are complicated may have many parts, but those parts are joined, one to the next, in relatively simple ways: one cog turns, causing the next one to turn…the workings of a complicated device like an internal combustion engine might be confusing, but they ultimately can be broken down into a series of neat and tidy deterministic relationships…”

A complicated system is predictable and understandable.

“Complexity, on the other hand, occurs when the number of interactions between components increases dramatically - the interdependencies that allow viruses and bank runs to spread; this is where things quickly become unpredictable.”

Think of the “break” in a game of pool. The cue ball strikes the balls in the rack, sending them flying.

Because of dense interactions, complex systems exhibit nonlinear change.

Team of Teams. Source: Gen Stanley McChrystal et al., Team of Teams, page 57

Chess is a great example. The game is rule bound, and the moves made by players are limited but interdependent. What happens to one piece changes the relationships between and behavior of the others.

There are 197,747 different ways for a player’s first two moves to transpire. By the third move, the possibilities rise to 121 million. By 20 moves, it’s more likely you’re playing a game that has never been played before.

A reductionist instruction card ala Taylorism would be useless for playing chess. The interactions generate too many possibilities.

Amplification

In complex systems, a problem is not just the product of a single, constant, identifiable factor. McChrystal says, “any number of seemingly insignificant inputs might - or might not - result in nonlinear escalation.”

Nonlinear escalation is unpredictable. It defies the neat and tidy clockwork vision of Taylorism.

“There are causes for the events in a complex system, but there are so many causes and so many events linked to one another through so many direct and indirect paths that the outcome is practically unpredictable.”

Complex systems are a double-edged sword. They’ve enabled the amazing exchange of ideas, information, and goods and services that define our contemporary world. They’ve enabled some amazing stories of entrepreneurial success. But, as McChrystal writes, bad actors have taken advantage of complexity, too.

“Other manifestations are devastating: terrorists, insurgents, and cybercriminals have taken advantage of speed and interdependence to cause death and wreak havoc.”

Complex systems are fickle and volatile, presenting a broad range of possible outcomes.

“We could not predict where the enemy would strike, and we could not respond fast enough when they did.”

The Task Force was stronger, more efficient, and more robust. But AQI was agile and resilient.

“When we realized that AQI was outrunning us, we did what most large organizations do when they find themselves falling behind the competition: we worked harder.”

Harder, but not necessarily smarter.

“Rank is used to assign authority and responsibility commensurate with demonstrated ability and experience. Leaders of higher ranks are expected to possess the skills and judgment required to deploy their forces and care for their soldiers.”

This old-school system had real world consequences.

“When a subordinate must spend time seeking detailed guidance from a distant officer in order to respond to a rapidly evolving opportunity, the price for traditional order and discipline becomes too high.”

It becomes, in McChrystal’s words, “Unacceptably slow.”

Part II

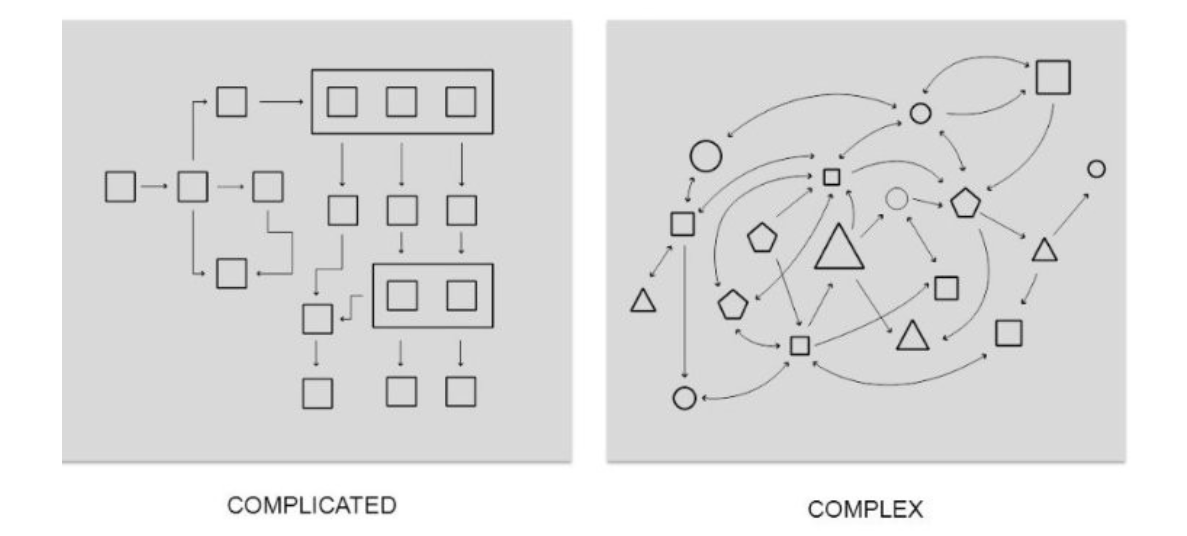

Realizing that the old-school, hierarchical command system based on rank was no longer working, McChrystal pushed a new way of organizing , one he calls “team of teams.”

“Team of Teams” is about working together to find solutions

It draws on the intuition and knowledge of everyone in the organization

It relies on familiarity, building trust, and empowerment

It relies on a common purpose that everyone can align to

The structure of the team is the strategy

This section of the book outlines a variety of places this kind of adaptable, trusting teamwork shows up in the real world today.

Sports

“Anyone who has ever played or watches sports knows that instinctive, cooperative adaptability is essential to high-performing teams.”

Think about fast-paced sports where the action is constantly evolving: basketball, hockey, or soccer, for example. To score, players have to know where their teammates are and where they will be, where the opposing team is and will be—and how the players on each team will react and respond as the game unfolds.

Sure, an individual superstar talent can help a team break the game. But it’s the ability of each player to know and trust their teammates that allows for success within the strategic framework established by the coaching staff.

Medicine

In the medical field, doctors providing emergency surgery are operating under a constant set of unknowns. Working as a single team, built on a foundation of knowledge and trust, is key to success in the operating room. As McChrystal puts it, “Nobody has an identical fracture [and] operations are unpredictable, you always have to adapt.”

Navy SEALs

SEAL training, as McChrystal says, “is impossible to survive by executing orders individually.” During training, prospective SEALs have a “swim buddy.” These pairs stick together in every scenario, even if it’s just to the mess hall.

A few key quotes about SEAL training:

“Groups like SEAL teams and flight crews operate in truly complex environments, where adaptive precision is key. Such situations outpace a single leader’s ability to predict, monitor, and control.”

“The trainees who make it through [SEAL training] believe in the cause…the believer will put his life on the line for you , and for the mission. The other guy won’t.”

“Without this trust, SEAL teams would just be a collection of fit soldiers.”

In all of these applications, the structure—not the plan—was the strategy.

Team of Teams. Source: Gen Stanley McChrystal et al., Team of Teams, page 129

In situations defined by a high level of interaction, ingenious solutions can emerge in the absence of any single designer. In other words, order can emerge from the bottom up. It doesn’t need to be directed from the top down.

McChrystal terms this: “joint cognition”

Part III

In part three, McChrystal breaks down how to achieve a nonhierarchical organization.

Nonhierarchical systems are a necessity in today’s world

Sharing information, knowledge, time, and physical space are critical components to deconstructing hierarchy to achieve adaptability

Giving everyone visibility into decision making empowers them to understand how leaders operate and how they can make their own decisions

To contend with complexity, everyone in the organization must see how everything works together. They have to understand the interdependencies and how the organization operates as a whole. When people understand these things, they make good decisions, quicker.

Here is a key quote from McChrystal:

“Functioning safely in an interdependent environment requires that every team possess a holistic understanding of the interaction between all the moving parts. Everyone has to see the system in its entirety for the plan to work.”

This doesn’t mean everybody should be able to do everybody else’s job.

“We did not want all the teams to become generalists—SEALs are better at what they do than intel analysts would be and vice versa. Diverse specialization abilities are essential. We wanted to fuse generalized awareness with specialized expertise.”

Time is another critical component. Seeing how the command and control structure failed to adapt quickly enough was key to McChrystal’s team of teams system.

“The organizational structures we had developed in the name of secrecy and efficiency actively prevented us from talking to each other and assembling a full picture.”

“When AQI operatives were captured, the network quickly ensured that everyone connected to the target would disappear. Our information had become useless.”

Physical spaces matters, too. You should organize your work spaces according to your goals. McChrystal sums it up well:

“How we organize physical space says a lot about how we think people behave; but how people behave is often a by-product of how we set up physical space.”

For example, you can promote interaction based on the paths employees have to take through your building. When employees have to walk through the cafeteria to get from one part of the building to another, they’ll bump into one another. These casual interactions promote familiarity and cross-pollination.

McChrystal provides a military example as well: the joint operations center (JOC).

A wall of screens at the front of the space showed live updates of ongoing operations.

“Anyone in the room—regardless of their position in the org chart—could glance up at the screens and know instantly about major factors affecting the mission at that moment.”

“My intelligence director, operations director, and senior enlisted adviser sat beside me and could see and hear everything I did.”

“The structure and symbolism of the Task Force’s new nonhierarchical space was critical”

Another example from the Task Force was the structure of the Daily Operations and Intelligence brief (O&I). The O&I established the battle rhythm, pumping information and context throughout our Task Force.

McChrystal explains the basic philosophy:

“One individual, properly empowered, became a conduit to a larger network that could contribute back to our process.”

As the O&I evolved, “Eventually we had seven thousand people attending almost daily for up to two hours….from all around the world.”

I love McChrystal’s insight into what made this effective (bolding mine for emphasis):

“…it allowed all members of the organization to see problems being solved in real time and to understand the perspective of the senior leadership team. This gave them the skills and confidence to solve their own similar problem without the need for further guidance or clarification. By having thousands of personnel listen to these daily interactions, we saved an invaluable amount of time that was no longer needed to seek clarification and permission.”

The initial imagery analyst would get the visceral satisfaction that her work had saved lives…

Running the O&I this way also helped teams become familiar with one another. It moved their working relationship from transactional to personal, and discouraged siloing or hoarding behaviors in the org.

Part of this was the Task Force’s embedding program. Take “an Army Special Forces operator and assign him to a different part of our force for six months, a team of SEALs for example, or a group of analysts.”

Implementing a non-hierarchical organization structure may seem daunting. But McChrystal and the Task Force reaped enormous benefits from this system. The trust this inspired built on itself.

“Once [people] could see why and how their assets were being used…” they started to reciprocate the behavior.

Part IV

This is probably my favorite part of this book. McChrystal is so impressive with his self-awareness and willingness to become a different kind of leader—the kind his team of teams and mission needed.

Leaders are not singular, heroic figures. They are generalists who must rely on the skills of their teams.

Today’s leaders must be “gardeners” and not “chess masters.”

Chess masters rely only on themselves to achieve their own goal.

Gardeners establish a successful environment in which their team achieves a shared goal.

High level leaders are generalists. They have to know about the full field of battle. This requires a change in perception of what leadership is. McChrystal (yes, the same General McChrystal) argues that high level leaders are gardeners.

A few great quotes illustrate McChrystal’s point:

“Being woken to make life-or-death decisions confirmed my role as a leader, and made me feel important and needed—something most managers yearn for. But it was not long before I began to question my value in the process...I began to reconsider the nature of my role as a leader.”

“The wait for my approval was not resulting in any better decisions and our priority should be reaching the best possible decision that could be made in a time frame that allowed it to be relevant. I came to realize that, in normal cases, I did not add tremendous value, so I changed the process.”

“The practice of relaying decisions up and down the chain of command is premised on the assumption that the organization has the time to do so or, more accurately, that the cost of the delay is less than the cost of the errors produced by removing a supervisor. In 2004 this assumption no longer held. The risks of acting too slowly were higher than the risks of letting competent people make judgment calls.”

McChrystal’s point is that, as leaders in a complex world, we must become comfortable with sharing power.

“An individual who makes a decision becomes more invested in its outcome.”

Sharing power is not an easy task. It requires a huge change in mindset. But it is absolutely necessary. A little insight into how the general went about it:

“Containing my desire to micromanage, I flipped a switch in my subordinates…”

“In the old model, subordinates provided information and leaders disseminated commands. We reversed it: we had our leaders provide information so that subordinates, armed with context, understanding, and connectivity, could take the initiative and make decisions.”

“I told subordinates that if they provided me with sufficient, clear information about their operations, I would be content to watch from a distance.”

McChrystal calls this “Eyes On—Hands Off.” He provides another great analogy related to U.S. Army uniforms and ranks:

“For most of my career in the Army, my mess dress uniform bore light blue lapels that signaled I was in the infantry. Artillery wore red, Special Forces wore green, tankers wore yellow. Our uniforms - stripes, badges, tabs, and insignia - announced our rank, qualifications, and experience, our boss in the org chart...when I was promoted to brigadier general in January 2001, my lapels changed to black - indistinguishable from those other generals who had ascended through the medical corps, engineers, or aviation. A general is expected to have general knowledge of the army - blue, red, green, and everything in between. It is because they have this general knowledge that leaders can be trusted to make major decisions.”

“In 2004 we were asking every operator to think like someone with black lapels.”

We gravitate towards “heroic leaders” and expect them to know everything. Of course, this isn’t possible! McChrystal pushed to “develop a new paradigm of personal leadership. The role of the senior leader was no longer that of controlling puppet master, but rather that of an empathetic crafter of culture.”

When faced with the complexity, “leaders themselves can be the limiting factor.”

Moving from “Chess master” to “Gardener”

Chess is the ultimate strategic contest between two players. Chess is often seen as an effective tool or analogy for learning strategic thinking. As McChrystal says, “The chess player is all by herself to observe, decide, and act.”

However, “war in 2004 followed no such protocol. The enemy could move multiple pieces simultaneously or pummeled us in quick succession without waiting respectfully for our next move.” AQI “had leveraged the new environment with exquisite success.”

Here’s the mindset shift: “Our leaders, including me, had been trained as chess masters. [But] we actually needed to let go.”

They needed to become gardeners.

“The gardener creates an environment in which the plants can flourish. The work done up front, and vigilant maintenance, allow the plants to grow individually, all at the same time.”

This relies on smart autonomy (think: plants or people acting on their own authority.) And it requires consistent maintenance.

“The gardener cannot actually “grow” tomatoes, squash or beans - she can only foster an environment in which the plants do so.”

I love McChrystal’s self-awareness and his ability to recognize that he needed to change his own definition of leadership.

“Although I recognized its necessity, the mental transition from heroic leader to humble gardener was not a comfortable one…But the choice had been made for me. I had to adapt to the new reality and reshape myself as conditions were forcing us to reshape our force...And so I stopped playing chess, and became a gardener.”

Gardening involves its own strategy—but its one that relies on setup and maintenance, rather than a mastermind anticipating and doing the right thing. McChrystal “needed to [shift] focus from moving pieces on the board to shaping the ecosystem.”

This involved “creating and maintaining the teamwork conditions needed” as well as a “delicate balance of information and empowerment.”

I love this quote: “Gardener plant and harvest, but more than anything, they tend”

McChrystal says the most powerful tool in his gardening kit was his own behavior. People watch and respond to how a leader acts. He focused on leading with personal touches that proved he trusted his teams—while providing a powerful model for them to emulate themselves.

Here are a few key takeaways from McChrystal’s experience visiting various battlefield locations and units.

“Greet them by their first name, which often causes them to smile in evident surprise.”

“As they briefed me, I tried to pay rapt attention. At the conclusion, I'd ask a question. The answer might not be deeply important, and often I knew it beforehand, but I wanted to show that I had listened and that their work had mattered.”

“‘Thank you’ became my most important phrase, interest and enthusiasm my most powerful behaviors.”

“I found it exhausting. But it was an extraordinary opportunity to lead by example.”

“I found …“I don’t know” was accepted, even appreciated.”

“Asking for opinions and advice showed respect.”

“I used ‘we’ to emphasize unity and teamwork.”

Part V

The last part of the book chronicles the taking down of Zarqawi.

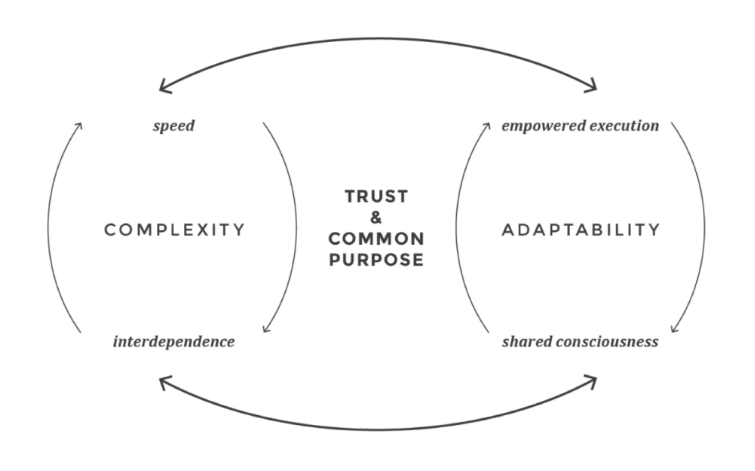

Zarqawi was a target, but AQI’s network structure reduced the efficacy of taking down a leader

The commander whose team identified Zarqawi knew that he was empowered to initiate a strike without asking permission

To adapt to a complex world, contemporary organizations and management must integrate web and node models

McChrystal discusses how the team of teams started to look ahead, adapt, and evolve.

“Across the network, teams coordinated the questions asked, shared the answers received, proffered suggestions, and exchanged insights. It was a battle of wits, and now we had harnessed thousands of minds—nobody's brain had been left in the footlocker.”

Team of Teams. Source: Gen Stanley McChrystal et al., Team of Teams, page 245

The time had come—the Task Force had found Zarqawi. (Bolding mine for emphasis.)

“We had talked for two and half years about this moment, but decision time is never as neat and clean as you envision it. Going after him was a given, but the question was how. The unit that controlled our operations in Iraq operated about thirty feet from me inside our headquarters at Balad. Their commander and I spoke briefly as he confirmed his confidence that the man was Zarqawi and said he intended to strike. He launched a raid from Baghdad, but as a backup also had F-16s ready to bomb. He didn’t ask permission and I didn’ ask him to ask. I’d learned that trust was critical.”

How amazing is this level of trust placed in junior officers? Still, the complexity of the AQI network meant this was far from the end.

“Though the elimination of Zarqawi represented a pivotal moment in our fight against AQI, it was just one small piece of the puzzle. In fact, the decentralization of authority that AQI had engineered—and that we, in our own way, had adopted—meant that “decapitation” was no longer a silver bullet. Our main strategy was to hollow out the middle ranks of the organization.”

As he concludes, McChrystal reflects on how these changes are part of broader shifts in information and organizational approaches around the globe.

“Human interaction—not just in the context of management—is changing tremendously.”

“Standards, norms, and rules of engagement make us comfortable. This is effective; this is efficient. Things should not look like a chaotic, self-organizing mess. And for the past century, those models have served us well.”

“We are likely to see more and more ‘chaotic mess’ solutions in the coming decades. We will need to confront complex problems in ways that are discerning, real-time, responsive, and adaptive.”

These insights aren’t just limited to the military world:

“Management determines the quality of the world we live in…organizations, armies, schools, government, corporations”

And he reflects on how the very conditions the Task Force had to contend with wound up being integrated into its operations:

“The Task Force still had ranks and each member was still assigned a particular team and sub-sub-command, but we all understood that we were now part of a network; when we visualized our own force on the whiteboards, it now took the form of webs and nodes, not tiers and silos. The structure that had, years earlier, taunted us from our whiteboards as we failed to prevent the murder of men, women, and children in attacks like the El Amel sewage plant bombing had, like Saddam’s bunkers, been repurposed to become our home.”

General McChrystal concludes:

“To defeat a network, we had become a network. We had become a team of teams.”

For more book summaries like this, subscribe to my newsletter!

About The Author

Emily Sander is an ICF-certified leadership coach with more than 15 years of experience in the business world and the author of Hacking Executive Leadership. She’s been featured in several print publications, online articles, and podcasts, including CEO Today Magazine, Leading to Fulfillment, and Leadership Powered by Common Sense.

Emily has a passion for helping business leaders reach their full potential. Go here to read her story from seasoned executive to knowledgeable coach. If you want to send Emily a quick message, then visit her contact page here.